Did you know that after Article 370’s abrogation in 2019, farmer suicides in Jammu & Kashmir dropped sharply, from 31 in 2019 to just 1 in 2020, 3 in 2021, and 1 again in 2022. What explains this dramatic decline?

The key lies in the cessation of the state’s Mandi Act following the abrogation. Farmers in J&K were no longer forced to sell exclusively within government-designated markets. The Mandi monopoly had ended.

Is the Mandi system really responsible for farmer deaths? The short answer is unequivocally yes. The pattern is clear not just in J&K, but also in multiple states where partial or full Mandi reforms have occurred.

The long answer, including exactly how the Mandi monopoly endangers farmers, follows.

The Mandi Monopoly

Among the very few things that economists agree upon is that monopoly is bad. But there is nowhere as absolute a monopoly as the one faced by Indian farmers. The Mandi is the king, and the only king, which they must serve to earn even the bare minimum.

Imagine this scenario: if a buyer tries to directly purchase even a kilogram of tomatoes from a farmer’s field, both parties would be committing an illegal act. Instead, the farmer is compelled to transport their entire harvest 20-50 kilometres to reach a government-designated market yard.

At these regulated markets, farmers also have low negotiating power. Licensed traders strategically delay purchases squeezing farmers into forced sales as perishable produce deteriorates. Farmers get low prices, consumers get poor quality, middlemen profit enormously.

Mandi monopoly creates an iron grip of middlemen on India’s agricultural supply chain, enabling them to systematically exploit both farmers and consumers.

The human cost of this monopoly becomes starkly clear when we examine the numbers.

The Data: Not Just J&K, But Across States

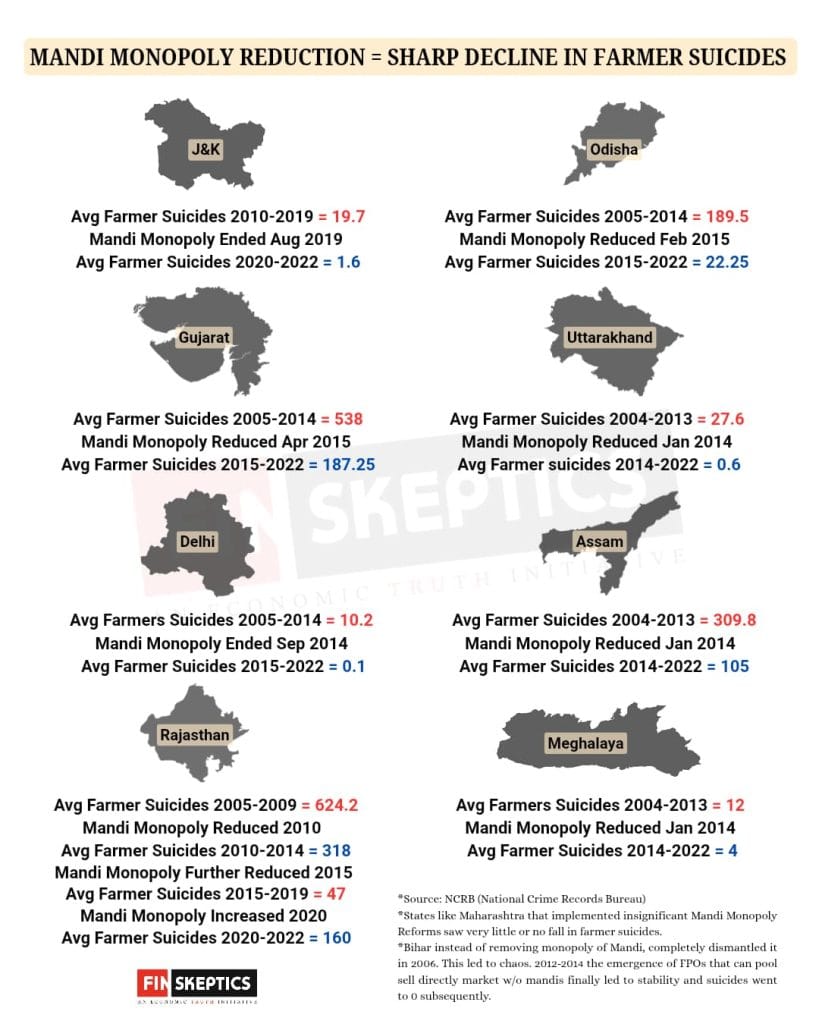

The dramatic turnaround in J&K is not an isolated case. After delisting fruits & vegetables from Mandi, Odisha’s farmer suicides fell from annual average of 190 to 50 in 2015 and 0 from 2017 onwards (per NCRB data).

Similar reforms in Gujarat in 2015 reduced farmer suicides average from 538 to 187. Uttarakhand farmer suicides dropped from an average of 27 to 0.

When Delhi removed Mandi regulations outside designated yards, suicides dropped from average of 10 to 0. Assam saw the average fall from 309 to 105 annually. The pattern is unmistakably clear wherever reforms have occurred.

Rajasthan provides a particularly instructive case. After implementing direct purchases outside Mandis’ purview in 2010, farmer suicides dropped from 851 in 2009 to 390 in 2010, and declined further. In 2015, with fees on fruits and vegetables removed, suicides fell from 373 in 2014 to 76 in 2015 and 43 in 2016. Yet in 2020, Rajasthan reversed course, reinstating Mandi controls over private yards and direct centres. Suicides surged from 26 in 2019 to 101 in 2020 and 239 in 2022.

The data is unequivocal. Reducing Mandi monopolies consistently saves lives. Increasing their reach increases farmer suicides.

But statistics alone do not explain why market restrictions literally kill. Let’s trace the deadly mechanism.

How Mandi Kills: Causation & Structural Trap

People often blame farmer suicides on debt, drought, or crop failure. But these are immediate symptoms, not the underlying cause.

In any business, survival during downturns depends on reserves built during better times. This is precisely where the Mandi monopoly inflicts its deepest damage.

By restricting farmers to selling only within designated yards and only to licensed traders, it ensures farmers operate on very thin margins. When a failed monsoon, bad crop, or family emergency strikes, there is no buffer between struggle and collapse.

Research consistently shows small farmers receive merely 6 to 10 percent of the final retail price, with intermediaries pocketing the remainder. Worse still, the same middlemen who underpay farmers often become their creditors, offering loans at interest rates as high as 36 to 60 percent annually. This vicious cycle of exploitation becomes, for many, an unbearable burden.

This changes when the restriction to sell only in regulated market is removed. Even if many farmers continue using Mandis, the presence of alternatives dramatically shifts power dynamics. Traders face competition, price realization improves, and middlemen lose leverage. Better margins enable farmers to save, repay loans, and weather tough seasons.

Bihar offers an instructive example. It abolished APMCs in 2006 without alternatives, causing chaos due to lack of aggregation and price discovery. When farmer cooperatives (FPOs) emerged in 2012-14, able to pool produce and, unlike other states, also sell directly in absence of Mandis, the outcomes improved and suicides dropped to zero. The lesson is clear: infrastructure helps, monopolistic coercion kills.

Ending the Mandi Monopoly: National Moral Imperative

Can we morally justify sustaining a system demonstrably deadly to farmers? Immediate and complete reform is not merely beneficial; it is ethically non-negotiable.

These monopolistic markets also severely distort India’s broader food economy, preventing direct trade and blocking vital market signals farmers need. This causes waste in some areas while others face shortages, as farmers base decisions on misleading cues from intermediaries rather than genuine consumer demand.

Breaking the monopoly immediately improves the system. Market transparency emerges, stabilizing prices and improving farmer incomes. Suicide rates plummet.

The freedom to sell produce is not an abstract privilege. It can literally mean the difference between life and death.