On the morning of May 18, 1974, deep beneath the sands of the Thar Desert in Pokhran, the ground shook. The message flashed to Delhi was cryptic but profound: “The Buddha has Smiled.” This was India’s first successful nuclear test.

The choice to conduct this test on Buddha Purnima, the birth anniversary of the apostle of peace, was not an accident; it was a message. It reflected a uniquely Indian strategic worldview: that Shanti (peace) is not passive idealism or strategic naivety.

True peace is secured through capability, restraint, and sovereignty. In 1974, Shanti meant possessing the ultimate deterrent so that India could never be coerced. It established that India would define its own destiny on the global stage, regardless of external pressure or technological denial regimes.

Fifty years later, the grammar of national security has expanded. Deterrence still matters, but it is no longer sufficient. In the twenty-first century, sovereignty rests equally on energy. A nation that cannot keep its factories running, its industrial corridors powered, and its servers cooled cannot claim strategic autonomy.

This is the philosophical ancestor of the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025. Just as Pokhran established India’s strategic autonomy in defence, the SHANTI Bill seeks to establish India’s strategic autonomy in energy and, by extension, in computation, industry, and growth.

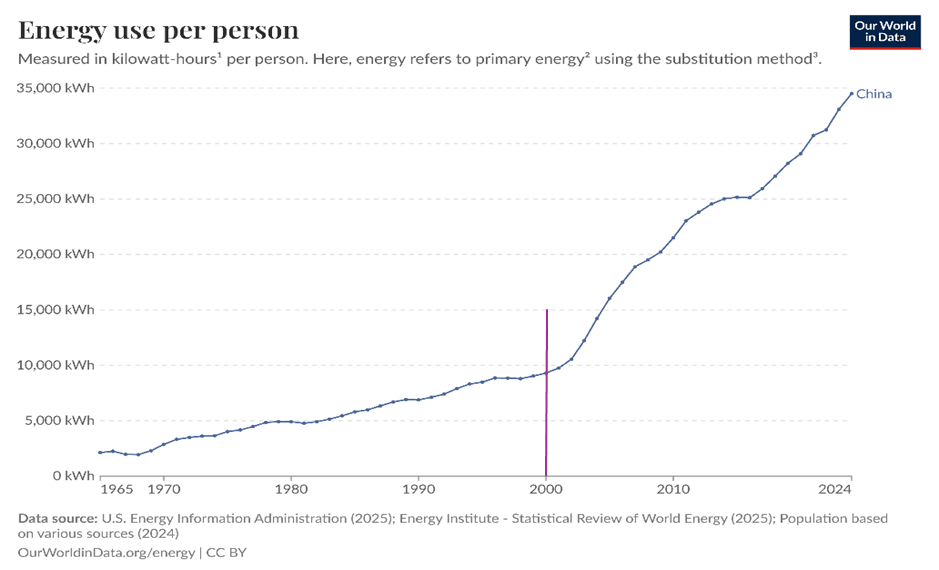

As countries industrialize, their energy demand does not rise linearly; it rises exponentially. Every phase of economic transformation, from heavy manufacturing to digital services, compounds electricity consumption. India now stands at that inflexion point. Growth is inevitable; energy scarcity is not.

What Is the SHANTI Bill?

India is entering a phase of structurally higher energy demand. To become a $5 trillion economy and achieve Net-Zero emissions by 2070, the country requires electricity that is continuous, predictable, and scalable. Solar and wind are indispensable to the transition, but their intermittency makes them structurally incapable of serving as base-load power for an industrial and digital economy that operates around the clock.

Traditional sources, while essential, face scaling constraints. Coal is environmentally untenable at the required scale, hydroelectricity is geographically and politically limited, and renewables demand massive storage and grid-balancing infrastructure that is still in the process of maturing. Nuclear energy is the only proven source capable of delivering clean, base-load power at the pace demanded by India’s growth trajectory.

This pattern is not unique to India. China’s post-2000 industrial surge was underwritten by an aggressive expansion of reliable base-load energy. Between 2000 and 2020, China’s electricity generation grew more than fivefold, enabling manufacturing dominance, export competitiveness, and eventually digital platform sovereignty. Energy abundance was not a by-product of growth; it was its precondition.

India today produces approximately 8.8 GW of nuclear power, accounting for less than 3% of total electricity generation. The national objective is to reach roughly 100 GW by 2047. Under the Atomic Energy Act of 1962, however, nuclear generation was restricted to public-sector entities, creating a structural bottleneck in capital mobilisation, execution speed, and technological induction.

Public-sector balance sheets alone cannot absorb the full capital expenditure required for a rapid scale-up of nuclear capacity without crowding out other national priorities. Simultaneously, international reactor suppliers remained hesitant under India’s earlier liability framework, which exposed them to unlimited downstream claims. The SHANTI Bill introduces a consolidated, modern legal architecture to resolve these constraints.

It repeals and subsumes legacy legislation into a single statute, ends the exclusive public-sector monopoly while preserving sovereign control over strategic materials, and rationalises liability provisions to unlock long-term domestic and foreign capital. The objective is not deregulation, but acceleration with control.

Compute Sovereignty

Nuclear energy in the SHANTI Bill is not framed merely as a solution for household electrification. Its strategic centre of gravity lies in compute sovereignty.In an economy where data, artificial intelligence, and digital public infrastructure increasingly define national power, uninterrupted electricity becomes a strategic resource. Data centres are among the most energy-intensive industrial assets ever built. Large-scale AI model training, inference workloads, semiconductor fabrication, and sovereign cloud infrastructure require low-variance, round-the-clock power.

As India builds its digital public infrastructure and positions itself as a global hub for AI and semiconductors, energy reliability becomes non-negotiable. Nuclear power is uniquely suited to anchor this ecosystem.

SMRs: Scaling Power Without Scaling Risk

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) sit at the operational core of this vision. Modern SMRs rely on passive safety architectures, gravity-fed cooling, natural circulation, and fail-safe shutdown systems that function without external power or human intervention. Their smaller cores significantly reduce the risk of meltdown, while underground or hardened containment structures enhance resilience against accidents, natural disasters, and sabotage.

Advances in waste management further reshape the historical risk calculus. Contemporary reactor designs achieve higher fuel burn-up, reduce total waste volumes, and enable safer dry storage of casks. Several systems permit partial fuel recycling, extracting additional energy while lowering long-term radiotoxicity. These technological shifts materially alter the assumptions that framed twentieth-century nuclear debates.

The SHANTI Bill anticipates a future in which captive SMRs directly power industrial clusters and data centres, insulating India’s digital backbone from financial systems to cloud infrastructure, from grid instability. Energy sovereignty thus becomes digital continuity, anchoring growth in reliability rather than contingency.

The Mechanics: How the Bill Works

Privatisation with Guardrails: Private Indian firms are permitted to build and operate nuclear reactors, expanding execution capacity and accelerating deployment. The state, however, retains exclusive authority over uranium enrichment, fuel fabrication, and waste custody. This preserves sovereign control over the most sensitive stages of the nuclear value chain while allowing private capital and managerial capacity to scale generation at speed.

The Liability Framework: The earlier liability regime imposed unbounded downstream exposure on suppliers, effectively deterring technology transfer and long-term investment. The revised framework aligns India with prevailing international conventions by capping operator liability in proportion to reactor size and restricting supplier liability to cases of wilful misconduct. Accountability is retained, but projects become insurable, bankable, and commercially viable.

Statutory Regulation: The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board is reconstituted as an independent statutory authority. This institutional separation between promoter and regulator strengthens credibility, enforcement capacity, and public confidence in a mixed public-private nuclear ecosystem.

Small Modular Reactors: The Bill explicitly prioritises factory-manufactured, transportable SMRs with shorter construction timelines and lower upfront capital requirements. The allocation of ₹20,000 crore for indigenous SMR development signals a strategic commitment to modular nuclear systems as the backbone of future clean, base-load power.

A Unique Hybrid Model

India’s approach does not replicate any single global template.

In the United States, nuclear generation is privately operated, with risk pooled through industry-wide insurance mechanisms. In China and Russia, the state controls the entire value chain and deploys nuclear exports as instruments of geopolitical influence.

India’s model combines private capital and operational efficiency with state control over the fuel cycle and strategic materials. This hybrid structure seeks to maximise speed and scale without compromising national security.

Strategic Benefits and Calculated Risks

The primary benefit is the accelerated addition of capacity. By broadening its capital base, India aims to transition from a single-digit nuclear contribution to a significant share of total generation within two decades. This reduces exposure to imported fossil fuels and buffers the economy against global price volatility.

The revised framework also enables access to advanced reactor technologies from partners such as France and the United States, facilitating domestic capability-building and localisation over time.

Risks remain. Liability caps inevitably imply contingent fiscal exposure in extreme scenarios, and regulatory effectiveness will be tested by large operators. These are governance challenges, not structural flaws, and their management will shape public confidence in the nuclear expansion.

Conclusion: Peace Through Strength

The SHANTI Bill returns to the original meaning of 1974: Peace Through Strength. For the citizen, ‘Shanti’ means the peace of mind that comes from reliability, stability and security.

It means economic confidence: reliable base-load power ensures factories operate without interruption, supply chains remain predictable, and employment is sustained. It means climate security: a decisive structural shift away from coal, thereby reducing the environmental and public health costs associated with urban pollution. And it means digital continuity: ensuring that the platforms, payment systems, and public digital infrastructure that now underpin daily life do not falter due to energy uncertainty.

The SHANTI Bill bets that the risk of a nuclear accident is manageable, but the risk of running out of energy is certain. It is a bold gamble to secure India’s future by embracing total state control, given the speed and scale necessary to power a rising global power.

In doing so, it reframes ‘Shanti’ for the present era: not passive reassurance, but stability earned through foresight, capacity, and control.