Taken from: https://zenodo.org/records/16950318

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a demographic reconstruction of the legitimate voter base in the Indian state of West Bengal for 2024. Drawing on official data from electoral rolls, census, and civil registration systems, we estimate the surviving voters from the 2004 base roll, additions through new cohorts (1986-2006 births), and adjustments for net permanent migration. Our findings indicate that the 2024 electoral roll may include approximately 1.04 crore excess voters– an inflation of 13.69%. We apply intentionally

conservative assumptions to establish a lower-bound estimate. The analysis has critical implications for electoral integrity and supports the case for a Special Intensive Revision in the state. Our methodology is replicable for nationwide applications.

Keywords: Electoral Roll Accuracy; Voter Registration; Demographic Audit; Survival Modeling; Migration; India Elections; Electoral Integrity; West Bengal

- Introduction:

The integrity of electoral rolls is foundational to the credibility of democratic systems. In representative democracies, the principle of ”one person, one vote” assumes that the electoral register faithfully reflects the eligible adult population. Inaccurate rolls, particularly those bloated with deceased individuals, duplicate entries, or fictitious voters, can severely distort electoral outcomes and erode public confidence in democratic institutions. This concern has become especially salient in large, dynamic democracies such as India, where internal migration, demographic transitions, and administrative bottlenecks challenge the robustness of electoral infrastructure.

The Election Commission of India (ECI), under the mandate of Article 324 of the Constitution and the Representation of the People Act, 1950, is responsible for maintaining an updated and accurate electoral roll [Election Commission of India, 2024]. While routine annual revisions are mandated, the Commission also undertakes Special Intensive Revisions (SIRs) when systemic anomalies are suspected. The last such SIR in West Bengal occurred in 2002, forming the foundation for the 2004 electoral roll [Election Commission of India, 2004]. In the absence of any subsequent large-scale verification exercise, the current state of the roll remains under scrutiny.

Recent political and administrative developments have heightened interest in electoral roll quality in West Bengal. The state is scheduled for a revision exercise in 2025, amid growing civil society concerns about over-registration and voter duplication. These concerns are not without precedent: international best practices, as articulated by the Venice Commission and International Foundation for Electoral Systems, stress the necessity of regular and transparent voter register audits to uphold electoral credibility [Venice Commission, 2002, International Foundation for Electoral Systems, 2015].

Despite its salience, India lacks a formal mechanism to routinely audit voter lists using demographic benchmarks. Most assessments rely on anecdotal evidence or post election turnout anomalies. This paper addresses that gap by employing a systematic demographic reconstruction to estimate the legitimate voter base in West Bengal as of 2024. Our approach triangulates survival modeling of the 2004 electoral roll, additions through new voter cohorts born between 1986 and 2006, who were not part of 2004 voter rolls and would have turned 18 year before or in 2024 and adjustments for net permanent migration using official census and registration data.

Importantly, our methodology is intentionally conservative at each stage. This allows us to generate a lower-bound estimate of the legitimate voter population. We then compare this figure to the official electoral roll published by the ECI for 2024.

Our central finding is that West Bengal’s 2024 voter list may contain over 1.04 crore excess entries, representing a 13.69% inflation above the estimated legitimate electorate. Given the magnitude of this discrepancy—and its potential to distort electoral outcomes in a politically competitive state—the implications for electoral integrity are profound.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on voter registration quality and demographic auditing methods. Section 3 outlines the data sources and estimation framework. Section 4 presents the results of our reconstruction. Section 5 discusses the conservative biases embedded in our assumptions. Section 6 explores policy implications and reform options. Section 7 concludes with recommendations for further research and institutional response.

2. Literature Review:

Accurate electoral registers are widely recognized as a foundational element of democratic infrastructure. In both established and emerging democracies, the quality of the voter roll shapes public confidence in elections, affects turnout, and may influence the legitimacy of electoral outcomes. The literature on electoral administration increasingly views the integrity of voter registration as not merely a technical issue but one that intersects with state capacity, citizen inclusion, and political contestation [Birch, 2011, Lehoucq, 2003].

2.1. Conceptualizing Electoral Roll Integrity

Scholars have classified voter list errors into two broad categories: inclusion errors (such as dead or duplicate voters) and exclusion errors (such as the omission of eligible citizens) [James, 2014]. These errors may arise from administrative lag, outdated civil registration systems, or politicized voter enumeration processes. While roll inflation is often associated with intentional manipulation, even unintentional over-registration can distort electoral margins in tightly contested regions.

International comparative studies have documented how the quality of electoral rolls varies across political and institutional contexts. In Latin America, the introduction of biometric verification and civil registry linkages has led to dramatic roll corrections, as seen in Brazil, where auditing led to a 12 percentage point reduction in the registered electorate [Hidalgo and Nichter, 2016]. West African countries have struggled with both under-registration and over-enumeration, with electronic reform initiatives producing mixed results due to capacity and design constraints [Piccolino, 2016].

2.2. Administrative and Political Challenges in India

In the Indian context, the task of maintaining accurate electoral rolls is complicated by the sheer scale and heterogeneity of the population. India’s federal electoral apparatus must contend with high rates of internal migration, variable performance in civil registration, and inconsistent voter enumeration practices across states. The Election Commission of India (ECI) has periodically undertaken Special Intensive Revisions (SIRs) to correct large-scale anomalies, but these are reactive rather than systematic in nature [Election Commission of India, 2004, 2024].

2.3. Demographic Audits: Tools and Limitations

A limited but growing body of work has evaluated the integrity of voter rolls by comparing registered voter counts with census-based or population-derived benchmarks. These assessments typically rely on ex post audits, statistical forensics, or macro-level registration-to-population ratios, rather than on prospective demographic reconstruction. For example, Myagkov et al. [2009] employ anomaly detection techniques, such as turnout-vote correlations and digit-based analysis, to uncover electoral manipulation in Russia and Ukraine. In contrast, Bratton [2013] highlights systematic discrepancies between official voter rolls and self-reported registration rates in survey data across African democracies, suggesting widespread under- and over-enumeration.

In the Indian context, despite the availability of rich demographic datasets through the Census and the Sample Registration System (SRS), such methods remain underutilized. Migration adjusted survival modeling-integrating cohort-wise mortality, fertility, and net migration flows-has yet to be systematically employed in electoral roll evaluation. A recent exception is Shekhar and Kumar [2025], who apply a demographic accounting framework to estimate legitimate voter counts in Bihar by reconstructing survivors from the 2003 roll, adding new eligible cohorts, and adjusting for permanent outmigration. Their analysis reveals a 9.7 percent inflation in the 2025 electoral roll relative to the reconstructed baseline, underscoring the value of demographic techniques in diagnosing voter roll integrity. Most other assessments in India continue to rely on administrative audits or field-level verifications, overlooking demographic estimation as a diagnostic tool. This methodological lacuna persists even as inter-state and intra-state migration intensifies, and as granular demographic microdata becomes increasingly accessible.

2.4. Positioning This Study

This paper addresses the empirical and methodological lacunae in the Indian literature by applying a rigorous demographic reconstruction framework to estimate the legitimate voter population in West Bengal. We rely exclusively on official public data, namely, the 2004 electoral roll (post SIR), CBHI birth records, SRS life tables, and Census migration statistics, to construct a lower bound estimate of eligible voters as of 2024. Unlike field-based surveys or static cross-sectional comparisons, our approach models the evolution of the electorate over two decades, integrating mortality and migration dynamics across cohorts.

By focusing on West Bengal, a state that has not undergone a Special Intensive Revision since 2002, we provide the first systematic estimate of potential roll inflation using demographic accounting. The methodology also offers a scalable template for electoral roll audits in other Indian states and federal democracies facing similar administrative asymmetries.

3. Data and Methodology

This study uses a demographic accounting framework to estimate the legitimate voter population in West Bengal as of 2024. The methodology combines three distinct but interrelated components:

(i) Estimation of survivors from the 2004 electoral roll using age-specific mortality data;

(ii) Addition of new voters born between 1986 and 2006 who survived to adulthood; and

(iii) Adjustment for net permanent migration between 2004 and 2024.

Each component is constructed using official data sources and conservative assumptions to yield a lower-bound estimate of the true electorate.

3.1. Data Sources

The analysis relies exclusively on publicly available data:

- Electoral Rolls: 2004 and 2024 rolls for West Bengal from the Election Commission of India [Election Commission of India, 2004, 2024].

- Mortality Data: Age-specific survival rates from the Sample Registration System (SRS) Abridged Life Tables (2011-2015 and 2018-2022) [Registrar General of India, 2015, 2022].

- Birth Data: Crude Birth Rates and estimated annual births from Central Bureau of Health Intelligence (CBHI) reports [Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, 2010].

- Migration Data: Census-based estimates of permanent in- and out-migration (2001 and 2011), extended to 2024 using CAGR extrapolation [Registrar General of India, 2011].

- Adult Population (2004 Aged Forward): Census 2001 age cohort distribution for West Bengal, aged forward by three years using survival probabilities to estimate the 18+ population in 2004.

3.2. Estimation Framework

We estimate the legitimate voter population in 2024, denoted by LV2024, using the following demo graphic identity:

LV2024registered = S2004→2024 + ρ × NV1986–2006 – NM2004–2024

Where:

- S2004→2024 is the number of survivors from the 2004 electoral roll;

- NV1986–2006 is the number of new voters who turned 18 between 2004 and 2024 and survived;

- N M2004–2024 is the net permanent migration out of the state during the same period;

- ρ is the estimated registration rate among eligible voters

3.3. Survivors from the 2004 Electoral Roll

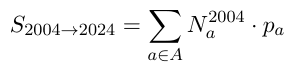

We begin with 4.74 crore registered voters in 2004. Age disaggregation is inferred from Census 2001 proportions for adults (18+). For each age group a ∈ A, we denote N2004 a voters in that group, and pa as the 20-year survival probability. Thus,

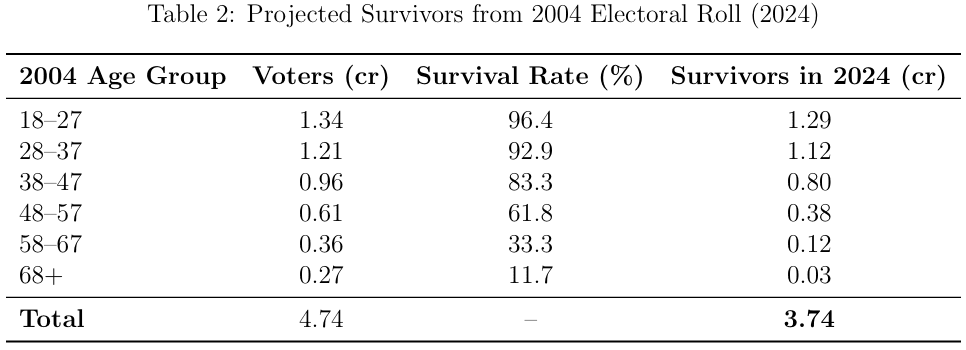

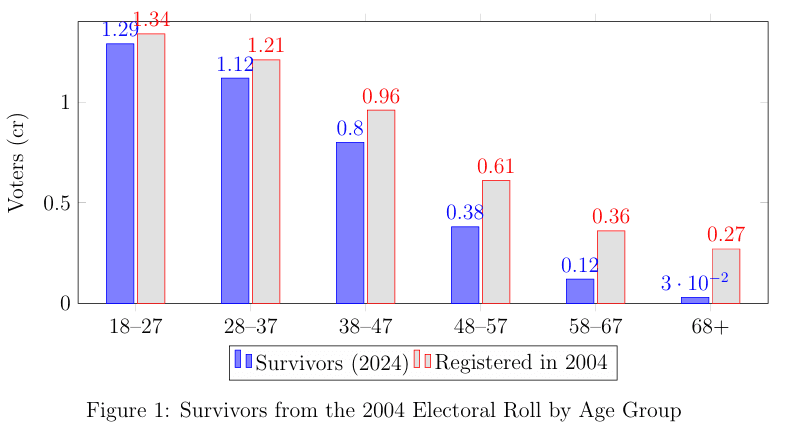

Survival rates pa are averaged across two SRS life table periods (2007-2011 and 2018 2022) to reduce noise and smooth over pandemic-induced shocks. For example, the survival probability for the 18-27 cohort in 2004 (aged 38-47 in 2024) is estimated at 96.45%, while for those aged 68+ in 2004 (88+ in 2024), it is 11.7%.

3.4. New Voter Additions: 1986–2006 Cohorts

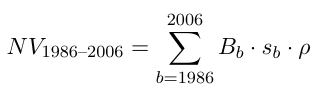

Next, we estimate individuals born between 1986 and 2006 who turned 18 between 2004 and 2024, survived to adulthood, and were registered as voters by 2024. Let Bb denote the number of births in year b, sb the probability of surviving to 2024, and ρ the assumed registration rate among eligible survivors.

We assume a registration rate of ρ = 0.928 (i.e., 92.8%) for all survivors who turned 18 in this period. This figure is based on observed voter registration levels of 91.3% in 2004 and 91.8% in 2011, extrapolated upward to reflect administrative improvements. The assumption is intentionally conservative, as it likely overstates actual youth registration, especially among migrants, women, and first-time urban voters, but helps generate a lower-bound estimate of excess registration.

3.5. Net Permanent Migration Adjustment

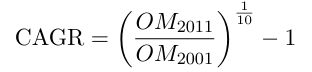

Permanent migration is computed using out-migration (OMt) and in-migration (IMt) figures from Census years 2001 and 2011. The Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) is calculated as:

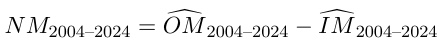

We then project values to 2024 and compute net migration as:

This approach assumes linear growth in migration patterns, likely underestimating actual out flows given evidence of post- 2011migration acceleration.

3.6. Conservatism of the Methodology

The entire estimation framework is designed to produce a lower-bound figure for electoral roll inflation. Key conservative assumptions include:

- Full legitimacy of the 2004 roll, with no prior inclusion errors.

- Linear extrapolation of migration trends, omitting post-2011 acceleration.

- Averaging of survival rates, including periods of lower mortality than recent reality.

- Voter Registration Rate (2024): We assume that 92.8% of eligible adults are registered to vote in2024. This is higher than historical registration levels in2004 (91.3%) and 2011 (91.8%) and is meant to conservatively inflate the estimated legitimate voter count.

Consequently, any discrepancy between the estimated and official voter counts represents a minimum level of roll inflation. The actual over-registration may be substantially greater.

4. Results

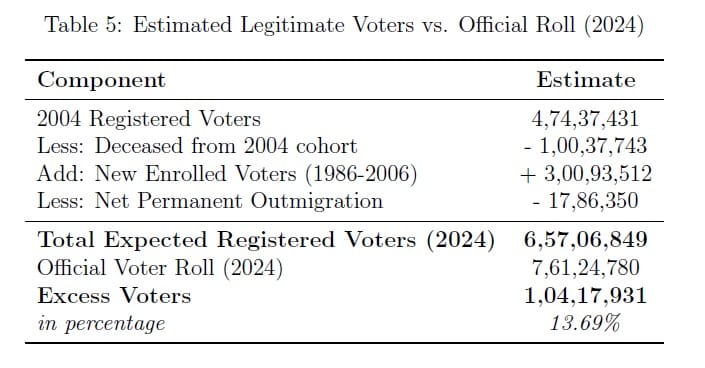

We now present updated empirical estimates of the legitimate voter population in West Bengal as of 2024,using the demographic reconstruction framework outlined earlier. The analysis proceeds in three steps: (i) estimation of survivors from the 2004 roll (ii) additions from new voter cohorts born between 1986 and 2006 (enrolled by 2024), and (iii) adjustments for net permanent migration. We then synthesize these components to estimate the overall voter roll inflation.

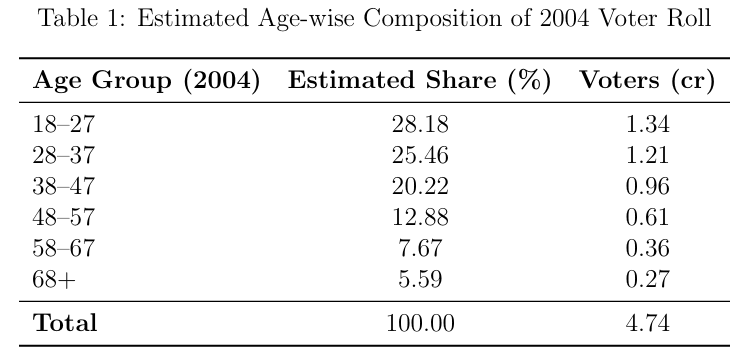

4.1. Cohort Distribution of 2004 Voter Roll

We reconstruct the 2004 age-wise voter base using Census 2001 age cohorts, aged forward by three years using SRS survival probabilities. This yields the following estimated age distribution for the 4.74 crore voters recorded in the 2004 electoral roll.

4.2. Survivors from the 2004 Electoral Roll

Applying age-specific survival probabilities over 20 years (from SRS lifetables), we estimate the number of 2004 voters who would be alive and eligible in 2024.

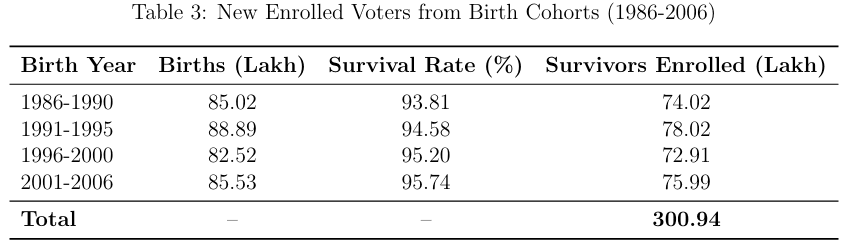

4.3. New Voter Additions (1986-2006 Birth Cohorts)

We now estimate the number of individuals who turned 18 between 2004 and 2024 and are still alive and registered to vote, using CBHI birth data, survival probabilities, and an assumed registration rate of 92.8%.

We thus estimate that approximately 3.01 crore newly eligible individuals would have enrolled between 2004 and 2024.

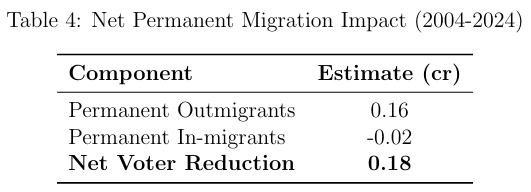

4.4. Adjustment for Net Migration (2004-2024)

Using Census 2001 and 2011 data and extrapolating via CAGR, we estimate net permanent out migration from West Bengal to be 17.86 lakh individuals during this period.

4.5. Synthesis: Estimated Legitimate Voter Base

We now combine all the components to estimate the total expected registered voter count in 2024.

These results imply that approximately 1.04 crore names, or 13.69% of the 2024 electoral roll, may not correspond to legitimately registered resident voters in the state. As noted throughout, our assumptions deliberately overestimate the legitimate count, suggesting that actual roll inflation may be even higher.

5. Discussion: Policy Implications and Robustness

5.1. Implications for Electoral Integrity and Administrative Reform

The finding of a potential surplus of more than one crore names, equivalent to 13.69% of the total electoral roll, raises serious concerns about the credibility of electoral administration in West Bengal. This degree of over-registration is not a marginal anomaly; it substantially exceeds the typical margin of victory in many constituencies and increases the vulnerability of the electoral process to fraud, impersonation, and political manipulation. Although the Election Commission of India (ECI) conducts annual summary revisions, these incremental updates may be insufficient to counteract structural inflation that has accrued over the past two decades.

A key policy implication is the urgent need for a Special Intensive Revision (SIR), especially in states where no such revision has occurred in over twenty years. West Bengal’s last SIR was conducted in 2002, and the 2024 roll rests on two decades of unverified additions, comprising both new cohorts and survivors from 2004. A fresh SIR would enable door-to-door verification, linkages with death records, and targeted purging of inflated pockets at the constituency level.

Beyond West Bengal, the findings underscore a systemic gap in India’s electoral infrastructure: the absence of a formal, demographic audit mechanism for voter rolls. Despite the availability of granular data from the Census, SRS, CBHI, and migration statistics, there is no institutionalized process for reconciling these datasets with the electoral register. The study suggests an urgent need for tighter integration of electoral data with civil registration databases, Aadhaar, and inter state migration records. Algorithmic checks for implausible entries, such as centenarian clusters or multi located registrations, coupled with quarterly demographic audits, could significantly improve roll accuracy and restore voter confidence.

5.2. Robustness of Estimates and Conservative Biases

The estimation framework employed in this study is deliberately conservative and designed to err on the side of overstating the legitimate voter population. This means that the 13.69% inflation we report should be understood as a lower bound, not a ceiling. The following key assumptions introduce systematic upward bias into our legitimate voter estimate:

- Baseline Legitimacy Assumption: We treat the 2004 electoral roll as fully legitimate, disregarding any potential pre-existing inclusion errors such as duplicate or fictitious entries.

- Survival Probabilities: We average across two SRS life table periods (2007–2011 and 2018–2022), thereby smoothing out the effect of mortality shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic. Using only the more recent life tables would likely yield lower survivor estimates and raise the inflation estimate.

- Registration Rate for New Voters: We assume a 92.8% registration rate among all survivors who turned 18 between 2004 and 2024. This is higher than the observed registration rates of 91.3% in 2004 and 91.8% in 2011. The assumption likely overstates actual enrolment, especially among young migrants, women, and urban youth.

- Migration Modeling: We project net permanent migration based on linear CAGR extrapolation from Census 2001 and 2011, assuming no acceleration after 2011. However, given growing inter-state labor mobility, actual outmigration may be higher, further reducing the expected voter base.

Taken together, these conservative biases imply that the true scale of voter roll inflation in West Bengal may exceed 13.69%, particularly if more realistic survival and enrolment rates are applied.

5.3. Scalability and Replicability

The methodology developed in this paper is not limited to West Bengal. It offers a scalable and replicable framework for demographic auditing of electoral rolls across Indian states, particularly those with high outmigration or historically weak roll verification processes, such as Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Odisha. The framework also holds broader relevance for other large democracies lacking systematic reconciliation of demographic and electoral data.

Future research may explore micro-level applications of this method using district-wise age pyramids, disaggregated migration data, and linkage with voter turnout patterns. Extending the model to incorporate urban–rural differentials, gender gaps in enrolment, and mobility-based voter duplication would enhance its diagnostic power.

6. Conclusion

This paper provides a conservative demographic reconstruction of the legitimate voter base in West Bengal as of 2024. By combining survival analysis of the 2004 electoral roll, enrolment estimates from birth cohorts turning 18 between 2004 and 2024, and adjustments for net permanent migration, we estimate that the official voter roll may contain over one crore excess entries. This corresponds to a roll inflation of 13.69%.

These findings raise urgent questions about the integrity of electoral administration in West Bengal and highlight the need for a Special Intensive Revision. More broadly, they point to the structural absence of a demographic audit mechanism within the Indian electoral system. The demographic accounting framework developed in this paper offers a scalable and transparent methodology for such audits and could significantly improve the accuracy of voter rolls, thereby strengthening public trust in democratic processes.

References

Sarah Birch. Electoral Malpractice. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Michael Bratton. Voting and democratic citizenship in Africa. Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2013.

Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. https://cbhidghs.nic.in/, 2010. Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Election Commission of India. Electoral roll of west bengal (2004). https://eci.gov.in/, 2004. Retrieved from official ECI archives.

Election Commission of India. Electoral roll of west bengal (2024). https://eci.gov.in/, 2024. Retrieved from official ECI archives.

F. Daniel Hidalgo and Simeon Nichter. Voter buying: Shaping the electorate through clientelism. American Journal of Political Science, 60(2):436–455, 2016. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12203.

International Foundation for Electoral Systems. Election audits: International principles that protect election integrity. https://www.ifes.org, 2015.

Toby S. James. Elite Statecraft and Election Administration: Bending the Rules of the Game? Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Fabrice E. Lehoucq. Electoral fraud: Causes, types, and consequences. Annual Review of Political Science, 6:233–256, 2003. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.6.121901.085655.

Mikhail Myagkov, Peter C. Ordeshook, and Dmitri Shakin. The Forensics of Election Fraud: Russia and Ukraine. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Giulia Piccolino. Infrastructural state capacity for democratization? voter registration and identification in cˆote d’ivoire and ghana compared. Democratization, 23(3):498–519, 2016.

Registrar General of India. Census 2011. https://censusindia.gov.in/, 2011. Office of the

Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.

Registrar General of India. Sample registration system: Abridged life tables 2011–2015. https://censusindia.gov.in/, 2015. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Registrar General of India. Sample registration system: Abridged life tables 2018–2022. https://censusindia.gov.in/, 2022. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Vidhu Shekhar and Milan Kumar. Demographic reconstruction and electoral roll inflation: Estimating the legitimate voter base in bihar, india (2025). SSRN, 2025.

Venice Commission. Code of good practice in electoral matters. https://www.venice.coe.int/, 2002 European Commission for Democracy through Law